How organic extra virgin olive oil from Madrid is produced

What is the first country that comes to mind when you think of extra virgin olive oil producers?

Non-Spaniards and people who do not live in Spain tend to say Italy first and Greece second. Of course, these are the olive oils that they mainly find in their local supermarkets. However, Spain is by far the biggest producer of olive oil in the world. It produces over half of the oil on the world market. Last season 1,598,900 tons were produced, 52% of the total. The province of Jaén alone produces more olive oil (685,491 tons) than all the European countries together, including Italy (265,000 tons) and Greece (225,000 tons). It’s just that the Italians and Greeks do a better job at marketing. The 4,040 tons produced in the Autonomous Region of Madrid only accounts for 0.25% of national production so it does not seem important. But, to my mind, the olive oil from Madrid is the best in the world! In this post, I will explain the secrets of its production.

What is virgin olive oil?

According to the International Olive Council (IOC), which is the only intergovernmental organisation in the world on which countries that produce or consume olive oil and table olives are represented, and is the supreme authority for the olive oil sector,

“Virgin olive oils are the oils obtained from the fruit of the olive tree (Olea europaea L.) solely by mechanical or other physical means under conditions, particularly thermal conditions, that do not lead to alterations in the oil, and which have not undergone any treatment other than washing, decantation, centrifugation and filtration.”(International Olive Council)

As I am no expert in this field, I consulted Pedro Andrés Álvarez and his father Pedro, an agricultural engineer, who own the oil mill called La Aceitera de la Abuela in Titulcia, a village in the south of the Autonomous Region of Madrid, to find out from them what these terms mean and what the process is like in real life.

The olive harvest

In general, there are three ways of harvesting olives. Each of them has different techniques and machinery. Which one is used depends on the type of tree and the terrain. Often, several methods are combined.

- Milking off: Milking off consists of picking the olives by hand, by grabbing the branches as if they were a cow’s teats and stripping off the olives by pulling down towards you. This is the method that causes the least damage to the tree and the fewest leaves and twigs in what is harvested. However, this method takes a long time and is very labour-intensive. It can only be used if you have very few trees, or they are in a place where a different method cannot be used. Today, “oscillating rakes” are also used for this job.

- Beating: long poles are used to hit the branches so that the olives fall onto a tarpaulin spread out under the tree. This method of harvesting can still be seen in many photographs. It also requires technique so as not to damage the tree (after all, you are giving it a beating) and not to pull off too many branches and leaves, which make the work harder at the oil mill.

- Trunk shaking: a tractor with an articulated vibrating head attached to a telescopic arm so it is easy to position draws up to the tree, encircles the trunk and puts a tarpaulin shaped like an upside-down umbrella under the tree. It then vibrates for about 20 seconds two or three times. The olives fall into the umbrella and roll down into a hopper. The tractor then empties them into a trailer.

Depending on the harvesting method chosen for the olive grove, the trees needed to be pruned differently. In the third case, for example, the branches should grow at a 45º angles from the trunk so that the shaking is transferred to them better.

One important point is that in Madrid it is forbidden to collect any olives that have fallen on the ground, to prevent any dirt from getting into the oil, which would lower its quality.

Also, it is very important for the entire process, from harvesting to storing the oil, to be finished as quickly as possible, so that all the qualities of the oil are preserved.

Receiving the olives

To ensure top quality oil, the freshly harvested olives are not stored but taken to be pressed immediately. From the trailer, the olives are emptied into a surge bin, which has a screen on top to collect the twigs and leaves. Under the surge bin is a conveyor belt that takes the olives to be cleaned and then weighed.

Weighing is another step to ensure the quality of the oil.

At La Aceitera de la Abuela between 3 and 5 kg of olives come in every day. Weighing, explains Pedro, is not only done for business reasons but is another quality control measure at the oil mill. All oil mills must record exactly how many kilos of olives, of what variety and from which grower (with their respective organic production certificates) enter and how many litres of oil exit. These meticulous records are sent to the Community of Madrid and the Ministry of Agriculture each month. This procedure prevents fraud, like the rapeseed oil scandal in the spring of 1981.

Hammer mill

Formerly, stone presses were used to crush the olives. Today, after being weighed, the olives go into another dosing bin, which feeds a hammer mill that crushes the olives to release their juice, the oil, from their cells. This step must not stress the olives. A uniform paste of olive pulp and stones is created, with the desired texture, from which the olive oil is extracted. To do so, the paste, which is called oily must, goes through a steel pipe into the malaxer (mixer).

The experience of the miller and the malaxation process are essential factors in the quality of the oil.

This stage is decisive, as it is here that one can see whether the owner of the oil mill prefers to produce higher quality oil or a larger quantity. The malaxing operation is needed to break down the oil and water emulsion. The tiny drops of oil in the oily must join together to form larger drops. The remaining solid paste is called “alperujo” (a mixture of pomace and vegetation water). This stage has three essential factors: the malaxation (mixing) time, the process temperature and the degree of acidity.

Malaxation time

The machine used, called a malaxer, consists of two steel cylinders, one inside the other. In the inner cylinder are paddles that slowly malax the paste for a certain length of time, usually no longer than 90 minutes. The longer the paste is mixed, the more oil is extracted but excessive mixing adds a slight taste of pomace (from the crushed olive stones) or of vegetation water (the dark, bitter liquid containing water and impurities that is produced during the olive crushing process) as the oil spends more time in contact with these. Therefore, it is the operator’s experience that counts here, as he must regularly test to see whether the paste has reach the ideal point, a balance of quantity and quality. So, at La Aceitera de la Abuela it is the elder Pedro who is in charge.

The degree of acidity

A third important factor, which is linked to temperature, is the degree of acidity. The higher the process temperature, the higher the acidity. However, for an oil to be classified as “extra-virgin”, its acidity cannot be over 0.8°. Because La Aceitera de la Abuela works at a temperature of between 17º and 20ºC, its arbequina oils have an acidity of only 0.09º. Laboratory analyses have shown that there oils are never over0.15º, even after a year in storage!

The temperature during the process

Water circulates in the outer cylinder to keep the paste at a specific temperature. This is another critical factor. To be classified as “extra-virgin” and “cold-pressed”, this operation must be carried out at a temperature below 27°C. If the temperature rises above 27°C, more oil is extracted but the wax content increases and the temperature-sensitive, volatile components that are responsible for the genuine fresh, harmonious fruity aromas of apple, herbs and banana break down. (I will write another post about the composition and chemical processes of olive oil.) When the resulting oil has an overcooked or burnt taste and smell and the aromas are lost, it can lose the classification of “extra-virgin”, even though laboratory analysis shows it is within the permitted values.

The influence of the variety of olive and its origins

At this point it should be noted that the degree of acidity also depends on the variety of olive, something that Man cannot alter. Arbequina is the olive with the least acidity. The origin of the olive also affects its degree of acidity; in other words, the composition of the soil in which the olive trees grow.

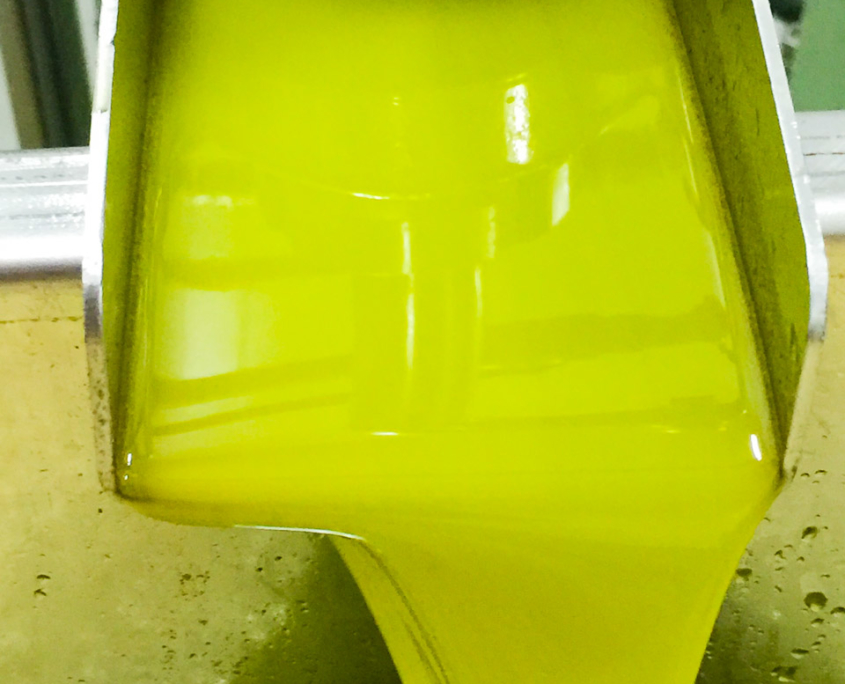

Centrifuging

After mixing, the oil must be separated from the pomace and vegetation water. Formerly this was done using hydraulic presses, in which the paste (or oily must) was spread in thin layers on mats. This was a slow system that had to be interrupted frequently for thorough cleaning so that the oil did not take on a taste of metal, fibre, esparto grass or vegetation water, etc. Therefore, at La Aceitera de la Abuela a decanter is used, which is simply a horizontal stainless steel two-stage centrifuge running at 3,000 to 4,000 rpm.

Using the centrifuge takes advantage of the fact that the immiscible liquids like oil and the water and solid material have different specific weights.

During centrifuging, the oil is continuously separated from the pomace/vegetation water mix and washing water and, as they are heavier, they are deposited in the tapered part of the cylinder and expelled through a valve. As the oil is lighter, it is pushed to the other end of the cylinder and led into another horizontal centrifuge.

Decanting

The oil that comes out of the centrifuge is still not completely clean. It tends to contain some water and impurities. It is therefore necessary to add another step to obtain pure oil. This stage is called decanting. Previously, decanting took place in tanks where the impurities and water were left to settle on the bottom of the tanks, which had to be cleaned out regularly. Being lighter, the oil floated on top of the deposits. This is a long process that leaves the oil in contact with the pomace for a long time, leading to a risk of transferring a taste of humidity and vegetation water to the oil. Using a horizontal centrifuge, which is based on the same technique as the previous one, the decantation time is limited to a minimum of an hour, preserving the fresh, fruity aroma of the oil.

Storage

After obtaining excellent oil, it must be preserved and stored until it is sold. Stainless steel tanks are used for this. However, when oil is taken out of the tank as it is used or sold, the oil level in the tank drops. Therefore, the upper part, above the oil, fills with air. Contact with air is not good for the oil as air causes oxidation, which reduces its quality. To prevent oxidation, nitrogen is pumped into the tanks and rests on top of the oil. In this way, the oil never comes into contact with the air until it is sold or used.

The sustainability loop is closed

In reality, the oil production process ends here but we have not yet seen what happens to the pomace and vegetation water that are expelled from the horizontal centrifuge. Formerly, for convenience, these waste products went to a secondary extraction factory. But at La Aceitera de la Abuela they have thought of everything: they invested in another machine that separates the pomace from the vegetation water.

The pomace is used as a heating fuel and the vegetation water goes through a composting process for approximately one year and is used as a natural fertiliser on the olive trees.

In short, all the stages of the process for producing extra virgin olive oil are purely mechanical and eco-friendly as no chemical products are used and no waste or CO2 emissions are produced.

After talking so much about extra virgin olive oil, would you like to try it?

Start with my favorite oil, the Arbequina variety.

Do you have any questions about the extra virgin olive oil production process?

Send me an email and I’ll be delighted to answer them!